- | F. A. Hayek Program F. A. Hayek Program

- | Regulation Regulation

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Corporate Voting

A Pandora’s Ballot Box or a Proxy with Moxie?

The recent financial crisis has prompted policy makers to reassess the guidelines and structures of corporate governance and shareholder rights. The authors discuss how new shareholder powers may

The recent financial crisis has prompted policy makers to reassess the guidelines and structures of corporate governance and shareholder rights. By focusing on the idea that corporations disregarded the wishes and demands of shareholders in order to advance the goals and ideas of management, legislators have aimed reforms toward increasing the accountability of the directors on corporate boards. Along these lines, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)1 and Senator Charles E. Schumer2 have proposed new rulings and legislation to alter the rules of proxy access voting during board elections. While corporate governance concerns may be valid, allowing shareholders to place board nominations on a company's ballot at little to no cost will bring considerable power to activist and dissatisfied shareholders. This power will create unintended consequences at the expense of the efficiency of corporations.3

PROXY ACCESS, THE SEC PROPOSED RULE, AND THE SCHUMER LEGISLATION

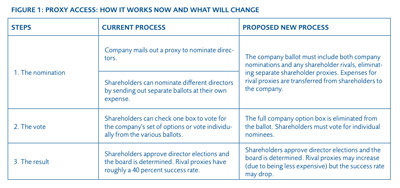

Traditionally, companies mail out proxies or ballots with nominations for their board of directors. Shareholders can vote for individual nominees or check a box for the full corporate slate of nominations. If shareholders (whether groups of individuals, hedge funds, or mutual funds) are dissatisfied with the company's performance, the actions of the directors, or the nominees, they must create, produce, and distribute an alternative proxy. These independent campaigns can be extremely costly, with thousands of dollars in mailing expenses alone. Directors are then determined using plurality voting laws, which means that nominees do not need more than fifty percent of the votes to win but rather the highest percent among candidates. This process of developing and distributing ballots is expensive in time and money for shareholders, thus discouraging consistent contestation of ballots.4

Many shareholder-rights activists see the traditional method as misrepresentative. In the press release accompanying the proposed rule on proxy access, the SEC raises the following concerns:

These concerns include questions about whether boards are exercising appropriate oversight of management, whether boards are appropriately focused on shareholder interests, and whether boards need to be held more responsible for their decisions regarding such issues as compensation structures and risk management. Because of these concerns, the Commission has decided to revisit whether and how the federal proxy rules may be impeding the ability of shareholders to exercise their fundamental right under state law to nominate and elect members to company boards of directors.5

The SEC proposed rule, known as Rule 14a-11, attempts to elevate these concerns by lessening the burden of proxy access to shareholders. The rule will allow shareholders to place nominees on the corporate ballot—eliminating the need for costly independent campaigns—and to propose changes in the disclosures and procedures of elections (unless these practices are prohibited by state law or corporate charter). Specifically, any shareholder owning at least 1 percent of the company can have access to the ballot and nominate up to either one candidate or 25 percent of the board, whichever is higher (see figure 1).6

The proposed ruling has resulted in a battle between shareholder (those who own the company) rights and management (those who run it) discretion. Where shareholder activists are concerned with failures of corporate governance, businesses are concerned about the potential for divisive directors, maximization of long-term shareholder wealth, short-term wealth extraction, and the furtherance of special interest or corporate social-responsibility goals by way of the corporate ballot. Additionally, the Chamber of Commerce brought the SEC's authority into question when it cautioned SEC's action prior to the amended legislation, stating that shareholder rights in nominations are within the bounds of state, not federal, regulation.7

Senator Charles Schumer from New York has presented legislation on shareholder rights which would solidify the SEC's right to regulate proxy access. The law will amend Section 14A of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to read, "The Commission shall establish rules relating to the use by shareholders of proxy solicitation materials supplied by the issuer for the purpose of nominating individuals to membership on the board of directors of an issuer."8 The Schumer bill is being reviewed by the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs and is unlikely to be passed into law before the SEC's November vote on proxy access.

THE UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES OF PROXY ACCESS

Reforming corporate ballot procedure to allow shareholders proxy access will result in unintended consequences, reducing the efficiency of corporations.9 First, shareholders are diverse and have varying, often conflicting interests. Corporate law traditionalists conclude that the case for increasing shareholder power is inherently flawed as a policy matter. The internal inconsistency of a shareholder's commitment to a company and the inconsistent goals of different shareholders make it extremely difficult for corporate lawmakers to make shareholders absolutely prime, even if that is the favored outcome.10 In engineering a legal regime, these policy makers would ultimately have to choose which type of shareholders the board members should serve: the day traders or the pensioners, the institutional or the small investors? Regulations that do not address the varying interests of investors fail to recognize the potential conflicts and complications once proxy access is easily and cheaply available.

Second, proxy access under the current plurality voting scheme—where the candidates with the highest number of votes win, regardless of whether they obtain a majority of the votes—may increase the power of organized special-interest groups. Plurality voting not only prevents the possibility of a failed election, but it also allows for the possibility of electing candidates who only have small, but active support. Neither of the proposed reforms discuss this problem. Yet, it could easily be eliminated by implementing a different voting standard. We suggest that an outright majority voting scheme could be used for contested elections which would ensure that any nominee would have to obtain the approval of the voting bloc of large institutional investors that actively vote their shares. In case of a runoff election, investors could rank their voting preferences on the ballot.11

Third, a reduction in the cost of shareholder nomination campaigns may result in frequent and inessential nominations. As proxy voting now stands, dissenting investors must bear the brunt of the costs to challenging a corporate ballot by developing and paying for an alternative ballot and its distribution. The high costs ensure that only those organized shareholders who are genuinely dissatisfied with the company's management decisions and performance seek to challenge the ballot. By eliminating those costs, policy makers will encourage more active nominations from investors, even when companies maintain good corporate governance and performance. Similar to a subsidy, costless nomination will distort the value of ballot changes and increase the quantity and frequency of activism. This increased activism could lead to inefficient boards by limiting board member power and judgment, therefore reducing the incentives to attract bold, innovative, and efficient board members.

CONCLUSIONS AND PREDICTIONS

This analysis highlights the numerous consequences of implementing shareholder proxy access under the current plurality voting scheme. Due to the diverse interests of investors, proxy access will encourage active, organized shareholders over passive ones. This regulation, meant to provide accountability of corporate boards and ensure shareholder rights, will result in favoring one set of shareholders over others at the risk of discouraging good, independent corporate behavior.

The following are a few predictions about the development of corporate law and voting if these regulations and laws are passed in their current form:

- Expect that these victories by the shareholder-rights movement will add fuel to management decisions to sell out to private equity buyers that do not present the difficulties of accountability to disparate financial intermediaries (like hedge funds, mutual funds, etc.).

- Expect that as institutional investors gain negotiating leverage through victories in the shareholder-rights movement, activist hedge funds will make use of that leverage as well and their activity in that space will increase as they are able to acquire access to more capital.

- Expect that as financial intermediaries' power is linked to flow of capital into their coffers, future recessions and major shifts in Federal Reserve policy will have an effect on activist investor activity.

ENDNOTES

1. SEC, "SEC Votes to Propose Rule Amendments to Facilitate Rights of Shareholders to Nominate Directors," May 20, 2009, http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2009/2009-116.htm and http://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2009/33-9046.pdf. [hereafter: SEC Ruling]

2. Senator Charles Schumer, "S.1074: A bill to provide shareholders with enhanced authority over the nomination, election, and compensation of public company executives," The Library of Congress: THOMAS, May 19, 2009, http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d111:s.01074. [hereafter: Schumer Bill]

3. For further analysis on proxy access, see: J.W. Verret, "Pandora's Ballot Box, Or a Proxy with Moxie? Majority Voting, Corporate Ballot Access and the Legend of Martin Lipton Re-Examined," Business Lawyer 62, no. 3 (May 2007), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=970013#.

4. Jeffrey McCracken and Kara Scannell, "Fight Brews as Proxy Access Nears," The Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2009, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB125123103942758059.html.

5. SEC Ruling.

6. Ibid.

7. David T. Hirschmann, "Comment Letter: Facilitating Shareholder Director Nominations Release Nos. 33-9046; 34-60089; IC-28765 File No. S7-10-09," U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 3–5, http://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-10-09/s71009-181.pdf.

8. Schumer Bill.

9. "Far from the single owner of a building, the shareholders are a diverse and ever-shifting group of people and institutions, with differing interests and, in the case of institutional investors, differing obligations to their own diverse constituencies." Martin Lipton and Steven Rosenblum, "Election Contests in the Company's Proxy, An Idea Whose Time Has Not Come," Business Lawyer 59 (2003): 67, 68.

10. "Shareholders with private interests, however, might prefer the firm to pursue those interests at the expense of the interests they have in common with other shareholders." Iman Anabtawi, "Some Skepticism About Increasing Shareholder Power," UCLA Law Review 53 (2006): 561, 575. This is also observed by Stephen Bainbridge, "The Case for Limited Shareholder Voting Rights" UCLA Law Review 53 (2006): fn. 96, 634. Also, Martin Lipton refers to this problems as the "Myth of the Monolithic Shareholder" in Martin Lipton and William Savitt, "The Many Myths of Lucian Bebchuk," Virginia Law Review 93 (2007): fn. 4, 756.

11. For more information on the author's majority voting scheme, see the full proposal in J.W. Verret, "Pandora's Ballot Box, Or a Proxy with Moxie? Majority Voting, Corporate Ballot Access and the Legend of Martin Lipton Re-Examined," Business Lawyer 62, no. 3 (May 2007), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=970013#.

To speak with a scholar or learn more on this topic, visit our contact page.